London Bridge

London Bridge

“London Bridge” refers to various crossings over the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark, central London. Over its long history, the London Bridge has seen multiple iterations, from the first Roman crossing to the modern structure that is in place today. This article traces the origins and transformation of London Bridge, detailing its significance, evolution, and cultural impact.

Origins: The Roman Foundation (50 AD)

The history of London Bridge begins with the Romans, who founded Londinium (modern-day London) around 50 AD. The Romans constructed the first bridge as part of their military and road-building efforts to consolidate their conquest of Britain. This early bridge was likely made of timber, possibly of pontoon design, and offered a strategic shortcut across the Thames, connecting Londinium to important Roman roads like Watling Street, which linked southern ports to the town of Camulodunum (now Colchester) in Essex, then the provincial capital of Roman Britain.

Londinium grew as a significant trading hub, and its location along the River Thames was ideal for connecting inland and overseas trade. Archaeological evidence points to scattered Neolithic, Bronze Age, and Iron Age settlements near the Thames before the Romans, but Londinium flourished primarily because of the bridge. The first permanent timber bridge, constructed around 50 AD, allowed the uninterrupted movement of people, goods, and vehicles, cementing Londinium’s status as a crucial outpost in the Roman Empire.

Anglo-Saxon and Viking Influence (5th–11th Century)

With the fall of Roman rule in Britain in the early 5th century, Londinium was gradually abandoned, and the bridge fell into disrepair. The Thames, during the Anglo-Saxon period, became a natural boundary between the emergent kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex. By the 9th century, repeated Viking invasions prompted a partial reoccupation of Londinium. Some historians believe that the bridge may have been rebuilt during this time, possibly by King Alfred the Great, after his victory at the Battle of Edington in 878 AD.

Another plausible theory suggests that the bridge was reconstructed around 990 AD by King Æthelred the Unready to facilitate troop movements during his conflicts with the Danish king, Sweyn Forkbeard. The bridge played a significant role in the struggle between Anglo-Saxons and Vikings. According to skaldic poetry, it was destroyed in 1014 by Olaf, a Viking ally of Æthelred, in an effort to split the Danish forces controlling both sides of the Thames.

Norman Era and Medieval Developments (1066–1209)

Following the Norman Conquest of 1066, London Bridge was rebuilt multiple times. King William I is said to have rebuilt it, and his son, William II, repaired or replaced the structure again in the late 11th century. Unfortunately, the bridge was destroyed by fire in 1136.

It was during the reign of King Henry II in the late 12th century that London Bridge entered a new phase. Henry II established a monastic guild called the “Brethren of the Bridge” to oversee repairs. He also commissioned Peter of Colechurch, a chaplain and bridge warden, to build a new, more permanent structure in stone. This monumental undertaking began in 1176, and Colechurch’s work included the addition of a chapel dedicated to Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury who had been martyred in 1170. The chapel at the bridge’s centre became an important starting point for pilgrims journeying to Canterbury.

The construction of the stone London Bridge, completed in 1209, took over 30 years. The bridge had nineteen piers, linked by arches and topped by shops and residences. Houses had been a feature of the bridge since its earliest days, generating rent that funded its maintenance. The bridge quickly became a major commercial hub and one of London’s most vital thoroughfares.

The Medieval Stone Bridge: Commerce and Catastrophe (13th–16th Century)

The stone bridge was a crucial crossing and a bustling marketplace. In its heyday, London Bridge housed 140 shops and homes, many multi-storey shops, with shops on the ground floors and living quarters above. It was one of the city’s busiest shopping streets, and the wide variety of goods sold reflected the growing importance of London as a centre of trade. By the 14th century, the bridge’s merchants were predominantly haberdashers, cutlers, bowyers, and other skilled tradespeople.

However, the medieval London Bridge was also a hazardous crossing. Its nineteen arches, combined with protective “starlings” (piles driven into the riverbed to protect the piers), created severe currents and whirlpools. The river’s flow was so restricted that the difference in water levels on either side of the bridge could be as much as six feet. Navigating the bridge by boat was notoriously dangerous, and many vessels capsized while attempting to “shoot the bridge.”

Additionally, the bridge was subject to fire and decay. The most significant fire occurred in 1212, burning several arches and trapping many people on the bridge. The stone structure was difficult to maintain, and collapses were not uncommon. Despite its problems, the bridge remained vital to London’s economy and infrastructure.

Renaissance and Rebuilding (16th–17th Century)

The Reformation in the 16th century led to the dissolution of monasteries, and the Chapel of St. Thomas was converted into a private residence in 1553. Over time, the bridge’s wooden houses were replaced by sturdier structures, some as tall as six storeys. These new buildings extended further out over the river, adding to the congestion on the bridge.

By the 17th century, congestion on London Bridge was severe. A keep-left policy was introduced in 1722 to help manage the flow of traffic, a measure that may have contributed to the British tradition of driving on the left. Fires continued to plague the bridge, including one in 1633 that destroyed the houses on the northern end of the bridge, which ultimately served as a firebreak during the Great Fire of London in 1666, preventing the flames from spreading south to Southwark.

The 18th and 19th Centuries: Rennie’s Bridge

By the 18th century, London Bridge was in dire need of replacement. A competition to design a new bridge was held in 1799. Though a radical single-span design by Thomas Telford was considered, John Rennie’s more traditional design of five stone arches was chosen. Construction began in 1824, and the new London Bridge was completed in 1831, slightly upstream from the medieval site.

Rennie’s bridge was 928 feet long and 49 feet wide, with the main materials being granite from Haytor, Devon. When it opened in 1831, it was London’s largest and most modern bridge. However, within a few decades, structural issues emerged. By 1924, it was clear that the bridge was sinking—Rennie’s design could not accommodate the ever-increasing traffic and heavier loads brought about by modern transportation.

The Sale to Robert McCulloch and the Modern London Bridge

In 1968, London Bridge was famously sold to American entrepreneur Robert P. McCulloch for $2.46 million. Contrary to popular legend, McCulloch was fully aware that he was not buying the more iconic Tower Bridge. The granite blocks from Rennie’s bridge were dismantled, shipped to Lake Havasu City, Arizona, and reassembled to span a canal leading to an artificial island. The bridge was rededicated in 1971.

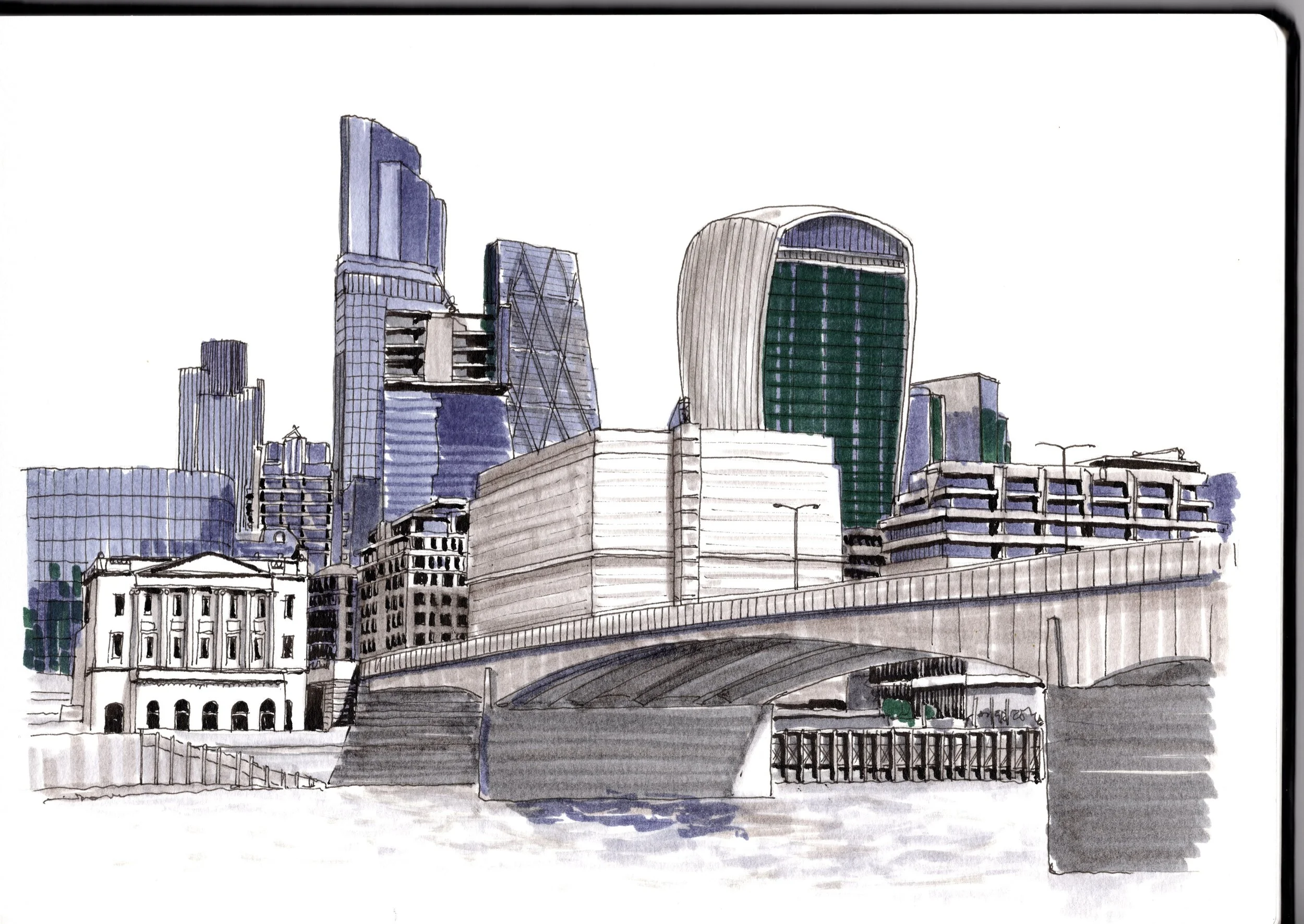

Meanwhile, the modern London Bridge, completed in 1973, was designed by Lord Holford and engineered by Mott, Hay and Anderson. This prestressed concrete box girder bridge spans 833 feet and was constructed adjacent to the old one, allowing traffic to continue crossing during construction. Queen Elizabeth II officially opened the new bridge on March 16, 1973.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

London Bridge has appeared in countless cultural references, from nursery rhymes like “London Bridge is Falling Down” to T.S. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land. The bridge’s many incarnations have witnessed more than 2,000 years of London’s history, from Roman Londinium to the sprawling metropolis it is today.

The medieval bridge, in particular, symbolised the city’s growth and a hub of commerce. For centuries, it was the only road crossing downstream of Kingston upon Thames, making it an essential artery for London’s development. Today, although the modern bridge lacks the architectural grandeur of its predecessors, it remains one of London’s busiest crossings and a testament to the city’s resilience and continual evolution.