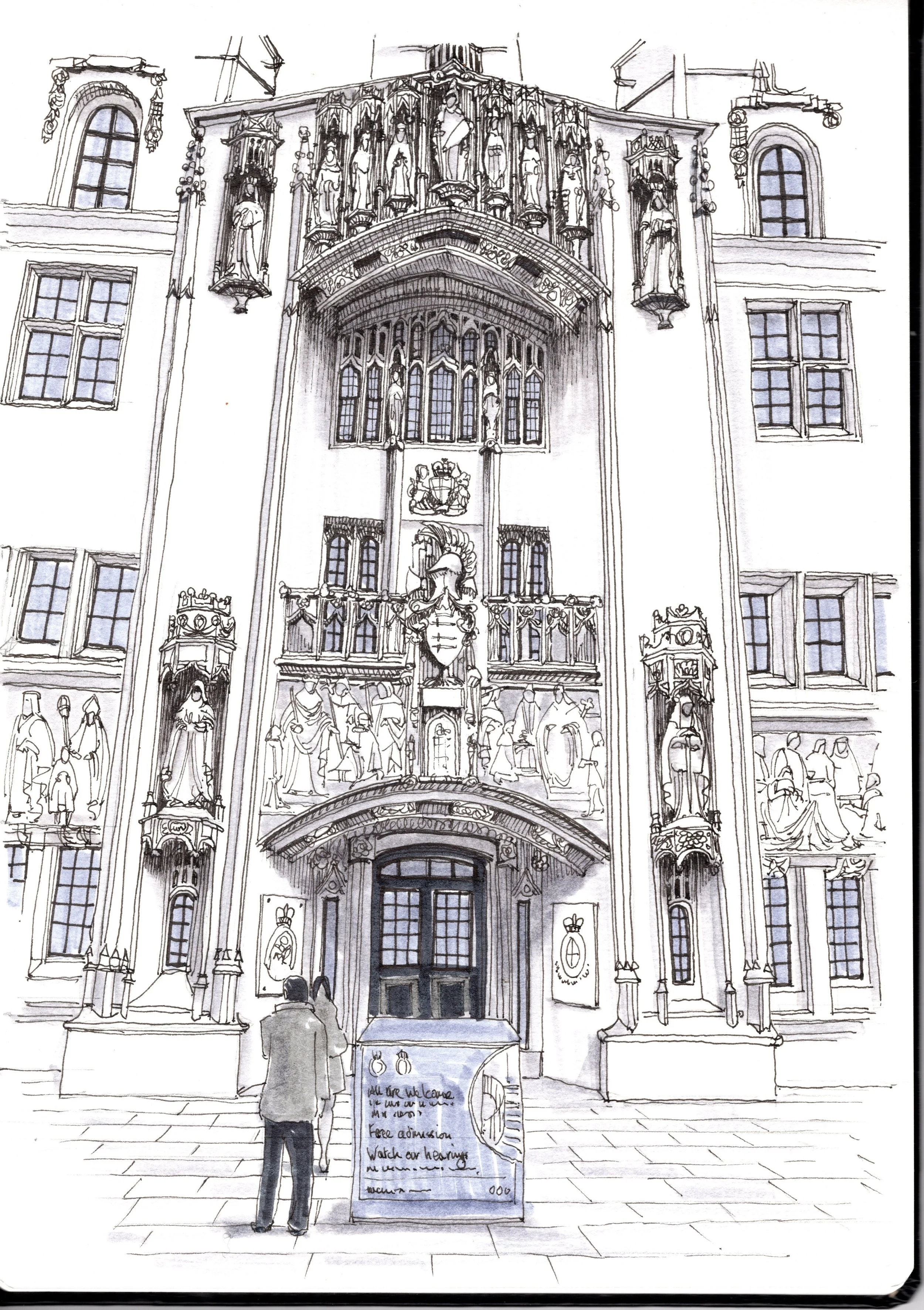

Supreme Court Westminster

Supreme Court - Westminster

The United Kingdom Supreme Court, often shortened to the UKSC, is the country’s highest Court of appeal for civil and criminal cases from England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. It handles significant public or constitutional cases affecting the entire nation. The Court is primarily housed in the historic Middlesex Guildhall in Westminster, which it shares with the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. However, the Supreme Court can, and sometimes does, sit in other locations across the UK, such as Edinburgh, Belfast, Cardiff, and Manchester.

Before the Supreme Court was established, the House of Lords carried out the judicial functions of the highest Court in the land. Specifically, the 12 judges, known as the Law Lords, handled appeals as part of the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords. They worked out of various rooms in the Palace of Westminster. However, the Constitutional Reform Act of 2005 called for a clear separation between the judicial and legislative branches, creating the Supreme Court to assume the Law Lords’ responsibilities. The move was finalised on 1 October 2009, when the Court officially came into existence.

Finding a suitable home for the new Court took some time. Several sites, including Somerset House, were considered, but the Middlesex Guildhall on Parliament Square was eventually chosen. This decision faced some scrutiny. A judicial review was launched by the conservation group Save Britain’s Heritage, and it was reported that English Heritage had been pressured to approve the necessary refurbishments. Despite these challenges, planning permission was granted, and the architects Feilden + Mawson, supported by Foster & Partners, began the renovation. Kier Group was appointed as the project’s main contractor.

Middlesex Guildhall itself has a rich history. Initially, it was used as the Middlesex Quarter Sessions House and later as the headquarters of Middlesex County Council. When the council was abolished in 1965, its council chamber was converted into a courtroom, now Court One of the Supreme Court. In 1972, the building officially became a Crown Court centre before its eventual transformation into the home of the UK Supreme Court.

While the Supreme Court is a vital part of the judicial system, its powers are somewhat limited compared to the highest courts in other countries, like the United States, Canada, or Australia. This is because the UK operates under a doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty, meaning that the Court cannot overturn any primary legislation passed by Parliament. However, it can strike down secondary legislation if it exceeds the authority granted by primary legislation. Additionally, under the Human Rights Act of 1998, the Court can issue a “declaration of incompatibility” if it believes that a piece of legislation conflicts with the European Convention on Human Rights. This declaration doesn’t automatically change the law but signals to Parliament that an amendment may be necessary.

The Supreme Court’s creation was part of a broader movement to clarify the roles of the judiciary, legislature, and executive branches. Before the Court’s establishment, the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords performed judicial functions, which blurred the line between the legislative and judicial branches. Although the Law Lords refrained from participating in political debates or legislation, they might later need to rule on. There was concern that the public did not always understand the separation. This lack of transparency about judicial independence was a key reason for the reform.

One of the leading proponents of the new Court was its first President, Lord Phillips of Worth Matravers. He argued that the old system confused people and creating a separate Supreme Court would ensure a clear division of powers. Another reason for the change was the practical issue of space in the Palace of Westminster. The House of Lords was under constant pressure for room, and moving the judiciary to a new building helped ease some of that strain.

However, not everyone was in favour of the change. Some argued that the previous system had worked well and that establishing a new Supreme Court would be unnecessarily costly. There were concerns that the Court could take on more power than its predecessor, with Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury, a future President of the Court, warning that judges might “arrogate to themselves greater power.” Lord Phillips acknowledged this possibility but believed it was unlikely.

Another argument against the reform was rooted in human rights. Some feared that mixing legislative, executive, and judicial functions—as had been done with the Law Lords—could conflict with the principles set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. If officials who make or enforce laws are also involved in interpreting them, there is a risk to the impartiality and independence of the judiciary.

Despite these debates, the reforms went ahead without considerable discussion in Parliament. A select committee of the House of Lords scrutinised the arguments for and against the creation of the Supreme Court, and the Government estimated that the setup cost would total £56.9 million. The new Court was ultimately established to provide greater clarity and independence in the UK’s judicial system.

In addition to its judicial duties, the Supreme Court remains a prominent part of the country’s legal framework, representing the final avenue for appeal in cases of public or constitutional importance. Its creation marked a significant change in how justice is administered at the highest level in the United Kingdom, offering a clear separation between the judiciary and other branches of Government while maintaining the country’s commitment to the rule of law.